CONTRIBUTORS

- Erin Nashira Binte Rudy Hedy

- Kamelia Tufah Kenchana Binte Suryakenchana

- Khin Mon Htoo

- Liu Wenchao

- Soh Chihiro

Suzann Victor is a Singapore-born, Sydney-based artist whose practice spans performance, installation, and public art. Engaging with human perception, materiality, and sensorial experience, she transforms spaces through light, water, the body, and physics to create immersive environments.

A pioneering figure in Singapore’s contemporary art scene, Victor co-founded 5th Passage (1991–1996), one of Southeast Asia’s earliest feminist artist-run initiatives. Based in shopping malls including Parkway Parade and Pacific Plaza, 5th Passage brought contemporary art into public, non-institutional spaces by engaging with the “readymade public” found in these commercial malls (Suzann Victor, personal interview, 20 September 2024). This approach not only generated new art audiences during a period without formal state arts funding, but also prefigured the institutional focus on public outreach that would later become widely adopted.

Following 5th Passage’s closure and a decade-long restriction on performance art in Singapore, Victor’s practice turned towards re-materializing absence as a form of resistance. Works like His Mother is a Theatre (1994) and Still Waters (1998) examined the contested nature of the performing body and the politics of visibility.

She was the first female artist to represent Singapore at the Venice Biennale (2001) and has exhibited at major international biennales, including the 6th Havana Biennale, the 2nd Asia-Pacific Triennial, and the 6th Gwangju Biennale. Her works are held in public and private collections worldwide, cementing her influence in contemporary art discourse.

DIALOGUES ACROSS TIME: NEW VOICES IN RESPONSE TO SUZANN VICTOR’S PERFORMANCE PRACTICE

Suzann Victor’s practice has left a lasting impact on Singapore’s contemporary art history. Her explorations of bodily agency and the politics of space remain deeply relevant. The challenges she once examined continue to resonate with artists today, shaping contemporary discourse across generations.

In this expanded dialogue with Victor’s performance-based practice, five emerging artists—Liu Wenchao, Erin Nashira, Kamelia Tufah Kenchana, Khin Mon Htoo, and myself, Soh Chihiro—respond to her seminal works through four new performances and a written reflection. Wenchao, Erin, Kamelia, and Khin engage with Postcard Boats (1998), Bloodline of Peace (2015), Still Waters (1998), and His Mother is a Theatre (1994) respectively, while I contribute this essay to examine both Victor’s original works and the reinterpretations they inspired. As the videographer for two of the performances, I developed a close familiarity with their nuances—insights that inform this writing alongside reflections from my own artistic practice.

Together, the performance works and this essay explore recurring themes—absence and presence, material and body, individual and collective experience—highlighting the sustained relevance of Victor’s inquiries within contemporary art. The following sections provide context to Victor’s original works before examining their reinterpretations.

Note: All quotes from Victor are extracted from her artist statements published on her official website.

Suzann Victor, POSTCARD BOATS, 1999 (detail). Photo: Courtesy of the artist

Postcard Boats (1999), Suzann Victor

Postcard Boats (1999) is a quiet yet profound work contrasting Victor’s larger-scale installations. Created during a residency in Snowdonia, Wales—where artists were encouraged to adopt fresh methodologies and thereby not allowed to bring their own materials—Victor adapted by purchasing postcards on trips into town. These idealized representations of country’s landscapes were folded into boats and released into the waters of the ocean surrounding Snowdonia. The postcards functioned both as a medium and a metaphor, engaging with ideas of national imagery, nostalgia, and how places are constructed and remembered.

The work also carried personal resonance, echoing Still Waters (1998), where Victor folded photographs into boats and placed them in water. In both works, the act of folding and releasing became a quiet gesture of remembrance—an intimate way of holding onto memory while simultaneously letting it drift away. The seemingly simple action of setting boats afloat evoked complex narratives of ephemerality, memory, and the passage of time.

Like much of Victor’s practice, Postcard Boats existed at the intersection of public and private, personal and political. It was, on one level, a poetic response to the workshop’s constraints, using postcards as a means to explore ideas of place and belonging. Yet beneath its simplicity lay deeper layers of significance—an exploration of how memories are carried, altered, and released over time.

Liu Wen Chao, A4 Paper Boat, 2024, site-specific performance at East Coast Park. Photo: Soh Chihiro.

A4 paper boat (2024), Liu Wen Chao

At first glance, Wen Chao’s response closely resembles Victor’s original performance, as he folds and releases paper boats into the waters of East Coast Park beach in Singapore. However, in conversation with him, it became clear that the work was not about re-enactment, but about engaging with the act itself. He described how, despite replicating Victor’s actions, the imperceptible elements—the emotions, the weight of memory, the nuances of movement—could never be fully recreated. Instead, his work became a reflection on the challenges of archiving something as ephemeral as performance. Documentation, no matter how detailed, will always be an Interpretation rather than an exact or faithful record.

This conversation resonated with my own artistic practice, which examines the body’s rhythms and archives them as responses to a particular time and place. Though I do not work in performance, the challenge of preserving an ephemeral experience is central to my approach. My work translates intangible bodily rhythms—such as sleep cycles—into material imprints. While these traces function as records, they do not fully replicate the experience itself but instead articulate its presence, capturing the body’s engagement with time in a tangible form.

Filming Wen Chao’s performance reinforced this tension between preservation and loss. While the camera documented the movement of the boats drifting away, it could not capture the stillness of the moment, the weight of his intentions, or the emotional depth of the experience. Postcard Boats was, for Victor, a deeply personal act, intertwining memory, place, and longing. Wen Chao’s response was not an attempt to recreate her emotions but to step into the gesture itself, engaging with what it means to perform an action that carries emotional history. What emerged was not a direct echo of the original, but a work shaped by his own context. In filming his performance, I became part of a layered process: the original performance, the act of reinterpretation, and the act of recording—each with its own timeline and emotional register. The result is not so much a replica as it is a continuation of Victor’s Postcard Boats—a layered response that speaks across generations, through bodies, and over time.

Bloodline of Peace (2015), Suzann Victor

Commissioned by the Singapore Art Museum to mark the nation’s 50th year of independence, Bloodline of Peace is an “invisible performance by a community of individuals whose blood provided the artwork with its corporeal materiality in all its bio-social, political, and symbolic dimensions” (Victor, 2015). Suspended from the ceiling, the work comprises 11,250 Fresnel lens units, each encasing a single droplet of blood donated by individuals from key communities—military, medical, civil defence, the arts, and the pioneer generation—through a highly-medicalised process.

Sealed between lenses, each droplet of blood functions as “tiny, yet rich and complex symbols of the sacrifice that Peace entails, and by implication, its fragility” (Victor, 2015). As Victor notes, peace is often defined by absence: the absence of war and bloodshed at the level of the nation, or conflict and turmoil at the level of the individual. Yet true peace is not passive—it requires ongoing “construction, education, and maintenance” (Victor, 2015). This labour is often carried out by armed forces, medical workers, and civilians alike. Bloodline of Peace highlights that a sustainable standard of life must extend beyond the provision of basic needs to include human rights and dignity. In this light, the artwork functions not only as a commemorative gesture, but as a living archive of collective contribution and a quiet interrogation of the structures that determine what peace is, and what it costs.

Suzann Victor, BLOODLINE OF PEACE, 2015 (exhibition view). Photo: Courtesy of Singapore Art Museum.

Erin Nashira, Erin Painting Peace, 2015. Photo: Soh Chihiro.

Erin Painting Peace (2025), Erin Nashira

Responding to Bloodline of Peace, Erin presents a performance rooted in relational presence. In this work, the artist and sitter paint each other’s portraits—a collaborative process that demands time, patience, and the willingness to truly see and be seen. As they paint, conversations unfold, revealing moments of intimacy. The resulting portraits move beyond simple representation; they become traces of the shared time and emotional exchange.

Like Victor’s work, Erin’s performance highlights the invisible labour required to sustain peace. In Bloodline of Peace, the biological act of giving blood embodies sacrifice and collective responsibility. Erin’s portraiture practice parallels this, revealing how even small, quiet acts of connection can carry emotional weight. The process often brings to light moments of self-reflection, discomfort, and emotional fragility. Yet rather than turning away, Erin’s work asks participants to stay—to witness, to make space, and to acknowledge one another fully.

As an observer, I see Erin’s work not as a direct reinterpretation of Victor’s, but as an extension of its ethics. Both performances offer care as a form of resistance: a quiet, sustained practice of presence that affirms our shared humanity. In doing so, they remind us that peace is not defined by the absence of conflict alone, but by the everyday ways we choose to engage—with empathy, attentiveness, and trust.

Suzann Victor, STILL WATERS (between estrangement & reconciliation), 1998, site-specific performance in 2nd floor drain at Singapore Art Museum (exterior view). Photo: Jason Lim.

Chums Air yang Tenang (2024), Kamelia Tufah Kenchana

Kamelia’s response to Still Waters considers the act of resistance within Singapore’s tightly controlled landscape, reflecting on how personal agency is negotiated within broader structures of power. After reaching out to the Singapore Art Museum for permission to perform inside the former museum grounds but receiving no response, she staged her performance outside, using reflections in water as a conceptual and visual parallel to the separation imposed upon her. Her work explores water as both an adaptable and disruptive force—fluid enough to slip through architectural constraints, yet, when amassed, capable of reshaping landscapes. This duality mirrors the ways marginalized voices navigate restrictive systems, finding alternative pathways to be seen and heard.

As the videographer for Kamelia’s performance, I observed how her presence was mediated by water, capturing the shifting interplay between restriction and agency. This process resonated with my own artistic investigations into spatial production and biopolitical governance in Singapore. In my practice, walking becomes a form of micro-resistance—subtly disrupting regulated rhythms to reclaim space and agency. In a city where efficiency and control often shape urban movement, walking offers an embodied way to cultivate meaningful relationships with the landscape and reflect on one’s place within it.

Victor’s performance was staged under similar conditions, during a period of heightened scrutiny on performance art. Instead of overt resistance, she used “water and the very architecture of the Singapore Art Museum to critique itself” (Victor, 1998), highlighting the tensions between state censorship and art making. In a similar way, Kamelia’s response shows how artists continue to negotiate imposed limitations, demonstrating that while restrictions may constrain, they do not suppress expression. This expanded dialogue between past and present reveals a persistent concern—how artists reclaim autonomy within regulated environments. Whether through performance, walking, or spatial intervention, the body remains a site of agency, adapting to and resisting the structures that seek to contain it.

Still Waters (1998), Suzann Victor

Still Waters (1998) is a site-specific performance staged in the drain of the Singapore Art Museum during the state-imposed restriction on performance art. As Victor explains, the work “used the museum’s architecture to critique itself” (Victor, 1998), highlighting the tensions between state censorship and contemporary artistic production. By blocking the drain’s openings to build up a body of water, Victor transformed it from a functional channel into a container of stillness—an act of resistance mirroring the regulated silencing of performance art.

Lying lengthwise in the water, Victor embodied these tensions physically—one ear submerged beneath the surface, enveloped in silence, while the other, above water, remain exposed to the chaotic sounds of the city. The contrasting temperatures heightened this experience: her submerged side was chilled by the water, while the exposed half was warmed by the tropical heat. The physicality of the performance thus embodied a psychological and somatic split, reinforcing the lived reality of restricting performance art.

The performance prompted not just a shift in attention, but a physical reorientation of the audience’s bodies—turning them away from the museum’s interior galleries to face the drain and the street beyond. Traditionally used to expel water and preserve the climate-controlled interior, the drain enacted a physical and symbolic boundary between the sanctified space of art and the external world. By occupying this marginal, unsanctioned site, Still Waters reconfigured the drain into a temporary “counter-site”—one that held not only water, but the presence of a restricted art form at the time (Victor, 1998). In doing so, the work quietly infiltrated the museum’s boundaries, revealing their provisional nature and reaffirming the capacity of performance to inhabit space, even under constraint.

Kamelia Tufah Kenchana, Chums Air yang Tenang, 2024, site-specific performance outside Singapore Art Museum. Photo: Soh Chihiro.

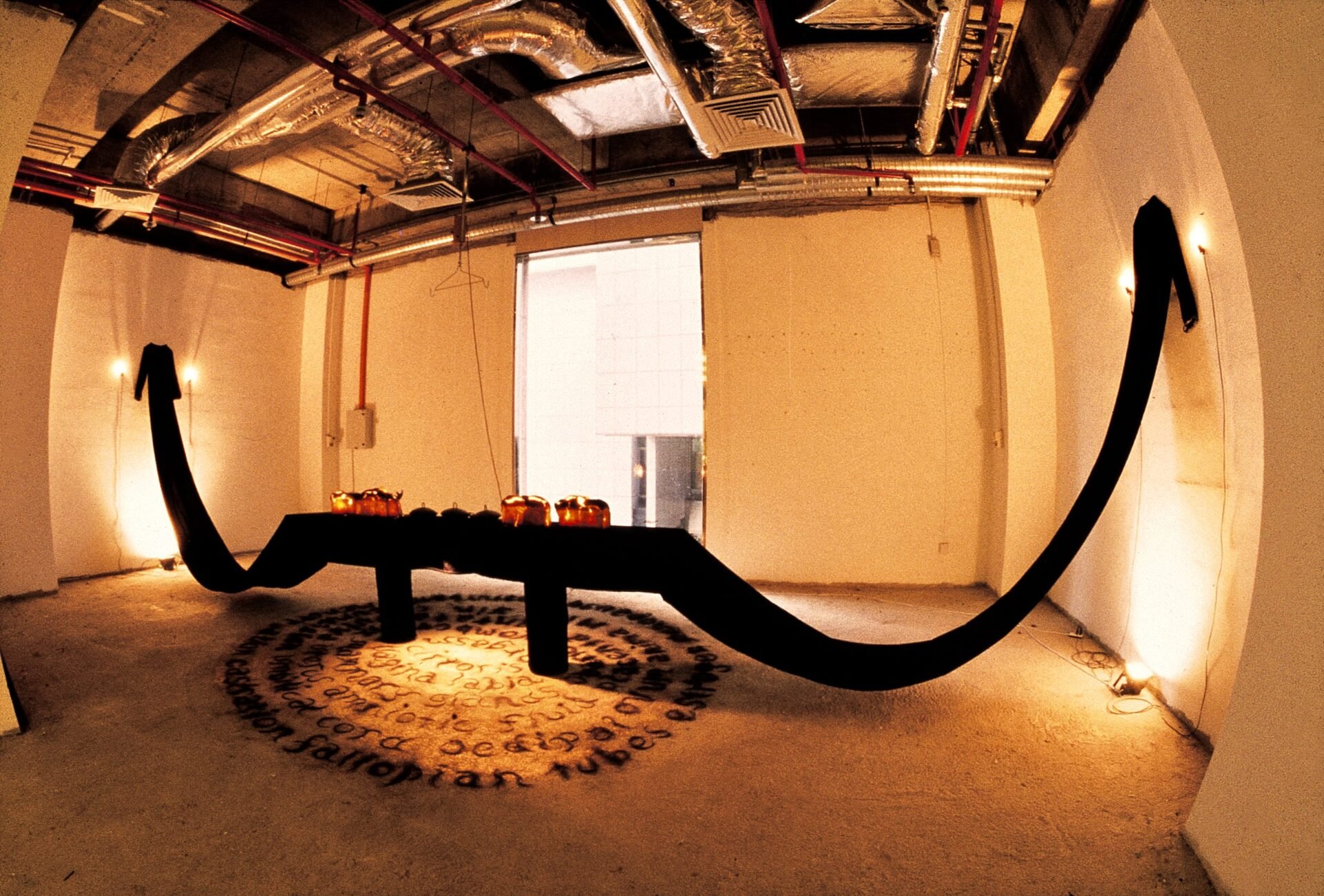

Suzann Victor, HIS MOTHER IS A THEATRE, 1994 (exhibition view). Photo: Chua Chye Teck

His Mother is a Theatre (1994), Suzann Victor

His Mother is a Theatre (1994) was produced during the state-imposed restriction on performance art, a period Victor describes as “one of the most important ruptures in Singapore’s art history, bringing about a form of disembodiment that produced a distinctly Singaporean cultural artefact—the absent body” (Victor, 1994). In response to new licensing requirements that demanded either a written script or an unaffordable SGD10,000 deposit, the work reinstates the censured body through its absence. Rather than submitting a script to the authorities, she submitted the body itself—as a fixed script composed of black human hair to “the public in Singapore’s de facto community space—the shopping centre” (Victor, 1994). Installed in Pacific Plaza, 5th Passage’s second home after their eviction from Parkway Parade, the hair script served as an embodied proxy for the female body in public space, reinscribing presence where it had been erased.

At the centre of the installation, words groomed from human hair spiral outward in concentric circles across the floor, spelling out the anatomical and physiological terms of the female body—including “clitoris”, “uterus”, “ovaries”, “menstruation”, and “placenta” (Victor, 1994). Through the act of reading, the audience engages in what Victor refers to as a “counter-performance”, as they become complicit in conjuring the image of the body that is removed from performance art. Above the script, “two seamlessly joined black garments hang in confrontation on opposing walls, draped over a table with hollowed-out bread loaves that were lit from within, causing them to both flow and release an aroma of toast” (Victor, 1994). Overhead, wok lids attached to a baby rocker produce clanging sounds, simultaneously activating the audience’s visual, auditory, and olfactory senses.

Framed within an empty shop lot in Pacific Plaza, His Mother is a Theatre presents “the body’s interior as an exterior, in a space and as a space that one enters” (Victor, 1994). The installation engages multiple registers of meaning, evoking “not only the entertaining distraction of commerce, the diorama of the anthropological museum, a film or stage set, but also the site of originary crisis” (Victor, 1994): Parkway Parade, where Ng’s Brother Cane took place, and which led to the decade-long absence of the performing body.

Khin Mon Htoo, re: theatre, 2024, site-specific performance at Pacific Plaza. Photo: Khin Mon Htoo.

re: theatre (2024), Khin Mon Htoo

In re:theatre (2024), Khin reflects on the female body. Her work explores the performative construction of self-identity and the multiple personas one cycles through over time. At the center of the work is a ceramic Fabergé-like egg, carrying twelve miniature, lethargic-looking babies—each representing an archetype drawn from Carl Jung’s Theory of Personality. Stained with old makeup, the egg rests on a pillow that is stuffed with the artist’s old clothes, referencing the theatrical nature of female performativity.

While the work centers on the cyclical nature of one’s identity, its visual form evokes associations with the female reproductive body, blurring the line between ornament and organ, object and flesh. In doing so, work becomes an extension of the self, drawing reference to His Mother is a Theatre, where hair forms a written script to conjure the image of the absent female body. Furthermore, staging the performance outside the former 5th Passage space allowed the work to engage with the surrounding urban environment, contrasting the exposure of a public space with the intimacy of a contained, performing body.

CONCLUSION

Through these responses, the continued relevance of Victor’s artistic concerns becomes evident. Across generations, artists continue to grapple with the complexities of presence, absence, materiality, and agency. While each reinterpretation is distinct, they all engage with Victor’s practice in ways that extend and deepen her inquiries.

This expanded dialogue is not simply a revisitation of Victor’s original works, but an archive of time—reflecting on the sociopolitical conditions under which her performances were first staged, and how they are now reimagined by artists navigating contemporary conditions. By engaging her works through new performances, the artists affirm that the questions she posed—about censorship, embodiment, and resistance—remain vital. In doing so, these works position Victor’s practice within the evolving discourse of Southeast Asian contemporary art, showing how past and present inquiries continue to intersect and shape one another.

ARTIST BIOS

Liu Wenchao (b. 1992) is a multidisciplinary artist and painter whose work is inspired by history and text. Originally from China, he moved to Singapore to expand his artistic practice and immerse himself in a new cultural environment. He graduated with a diploma in Fine Art from NAFA in 2014, specializing in oil painting, and later worked closely with performance artist Lee Wen at the Independent Archive.

Erin Nashira (b. 2001) is a contemporary artist based in Singapore. Her practice focuses on materiality and human connection, exploring themes of intimacy and emotional relationships. Through her work, Erin seeks to capture shared experiences and the nuances of personal bonds, inviting viewers to engage with themes of love, empathy, and connection.

Kamelia Tufah Kenchana (b. 2000) is a Singaporean multidisciplinary artist. With a background in performing arts and traditional Malay dance, Kamelia’s work explores themes of identity, culture, and personal narrative. Her practice integrates elements of movement and rhythm, embodying the fluidity of her heritage and artistic influences.

Khin Mon Htoo (b. 2002) is a Burmese multidisciplinary artist based in Singapore. Through figurative sculptures, Khin’s work explores contemporary social issues related to feminine identity, including the objectification and commodification of the female body. Her practice spans acrylic, printmaking, and watercolor, with a recent foray into whimsical ceramics.

[Written by]

Soh Chihiro (b. 2002) is an artist and arts manager based in Singapore. Her practice examines the relationship between the body and its environment, exploring how bodily rhythms unconsciously align, diverge, and interact with others. Rooted in rhythmanalysis, her work investigates nuanced ecological interconnectivities through movement, time, and spatial negotiation.

Bibliography:

STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery (n.d.) Suzann Victor. Available at: https://www.stpi.com.sg/artists/suzann-victor/ (Accessed: 25 February 2025).

Victor, S. (1994) His Mother is a Theatre [Installation]. Available at: https://suzannvictor.com/artwork/his-mother-is-a-theatre-1994/ (Accessed: 28 April 2025).

Victor, S. (1998) Still Waters (between estrangement & reconciliation) [Performance]. Available at: https://suzannvictor.com/artwork/still-waters-between-estrangement-reconciliation/ (Accessed: 28 April 2025).

Victor, S. (2015) Bloodline of Peace [Installation]. Available at: https://suzannvictor.com/artwork/bloodline-of-peace-2015/ (Accessed: 28 April 2025).