CONTRIBUTORS

- Amirah Zahirah Binte Abu Bakar

- Ho Rui Kai Aryton

- Neo Yue Ting

- Ng Jia Xi

- Shana Selvan

PRESERVING THE VANISHED LEGACY AND LOSS OF 5TH PASSAGE

Introduction

This essay strives to share a deeper insight into the intersection of the work of celebrated artist, Suzann Victor, with life. Victor’s practice is multidisciplinary and multilingual, spanning from large-scale kinetic installations to intimate performance works, often engaging with light, sound, the body, and space. Her multifaceted creations reflect an ongoing evolution in time, space, and being. Through her materials and experiences, Suzann has become a prominent figure in the contemporary art scene in Singapore and abroad. Like silent echoes, her fight for the evolving art ecosystem we are exposed to today remains buried. As emerging young artists, we find responsibility in understanding and bringing light to our foremothers who paved the way for us in discovering more avenues for artistic expression. Suzann Victor is one of many artists who changed the trajectory of art in Singapore. As a woman in a male dominated art movement in Singapore, we will explore the challenges, repercussions and resilience Suzann persisted through her life as an artisT.

Chapter 1: Early Beginnings

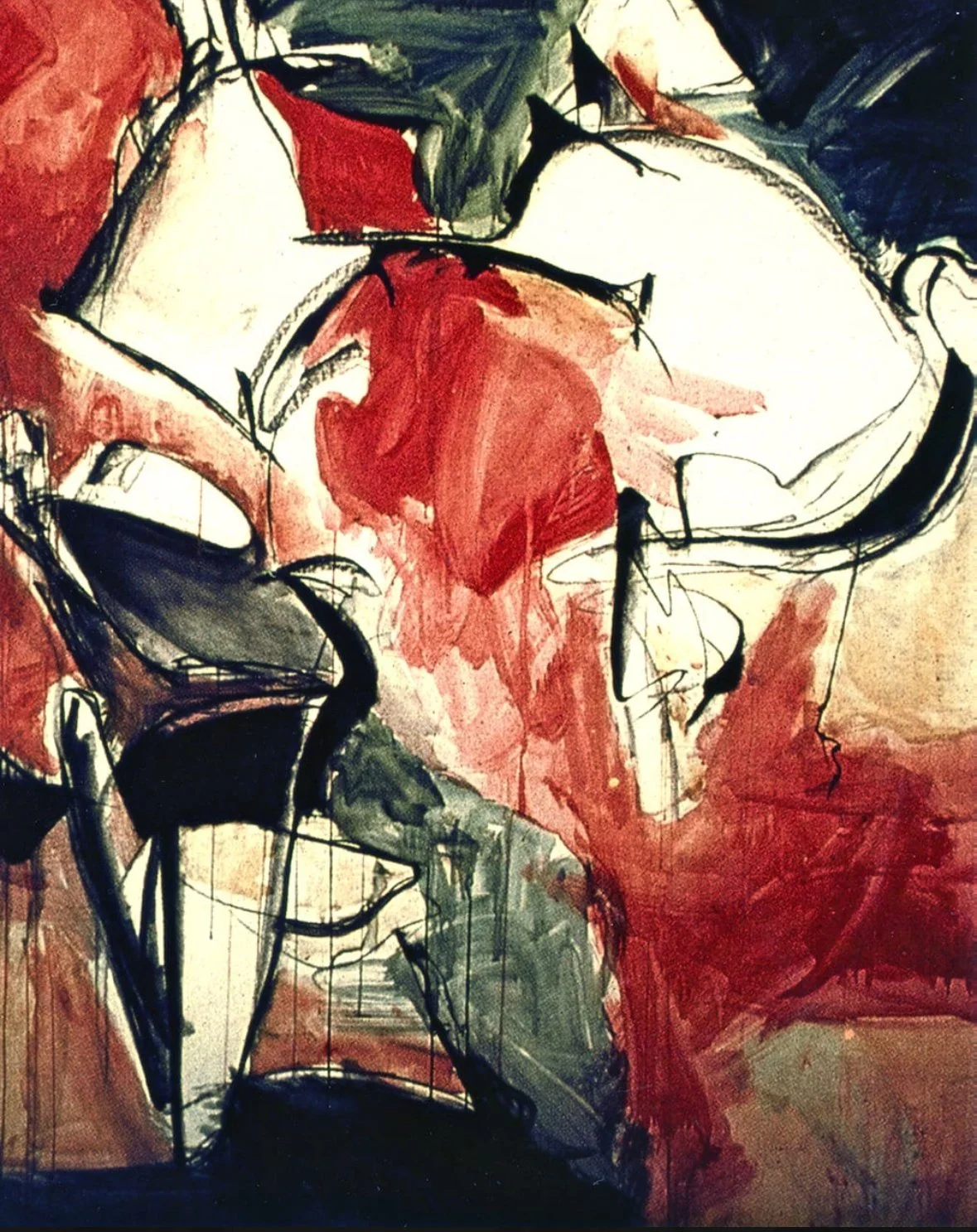

Born in 1959, Suzann Victor is a Singaporean artist currently based in Sydney, Australia. Tracing back to the genesis in her artistic practice, she started her early beginnings as a student of the Lasalle College of the Arts (Graduated 1990), where she majored in painting. Visually, her paintings evoke a sense of fluidity but also one of unease, as observed from the muted warm tones integrating with dark, bolder brushstrokes. This duality of colours and tone reflects life and experience, a theme she carries with her throughout her art practice.

Suzann Victor, ART OF COMMUNICATION, 1989, oil on canvas, 1.3 x 1.3m

Suzann Victor, GARDEN OF GETHSEMANE, 1989, acrylic & charcoal on paper, 1.4 x 2m

Her time as a student marked the beginning of her interest in conceptual and socially engaged art. She later co-founded Singapore’s first all-women art collective, which became a crucial platform for integrating the arts into public life and engaging directly with society. This was particularly significant during a period of rapid modernisation in Singapore, an awareness that grew alongside the early successes of her artistic career.

Chapter 2: Fifth Passage

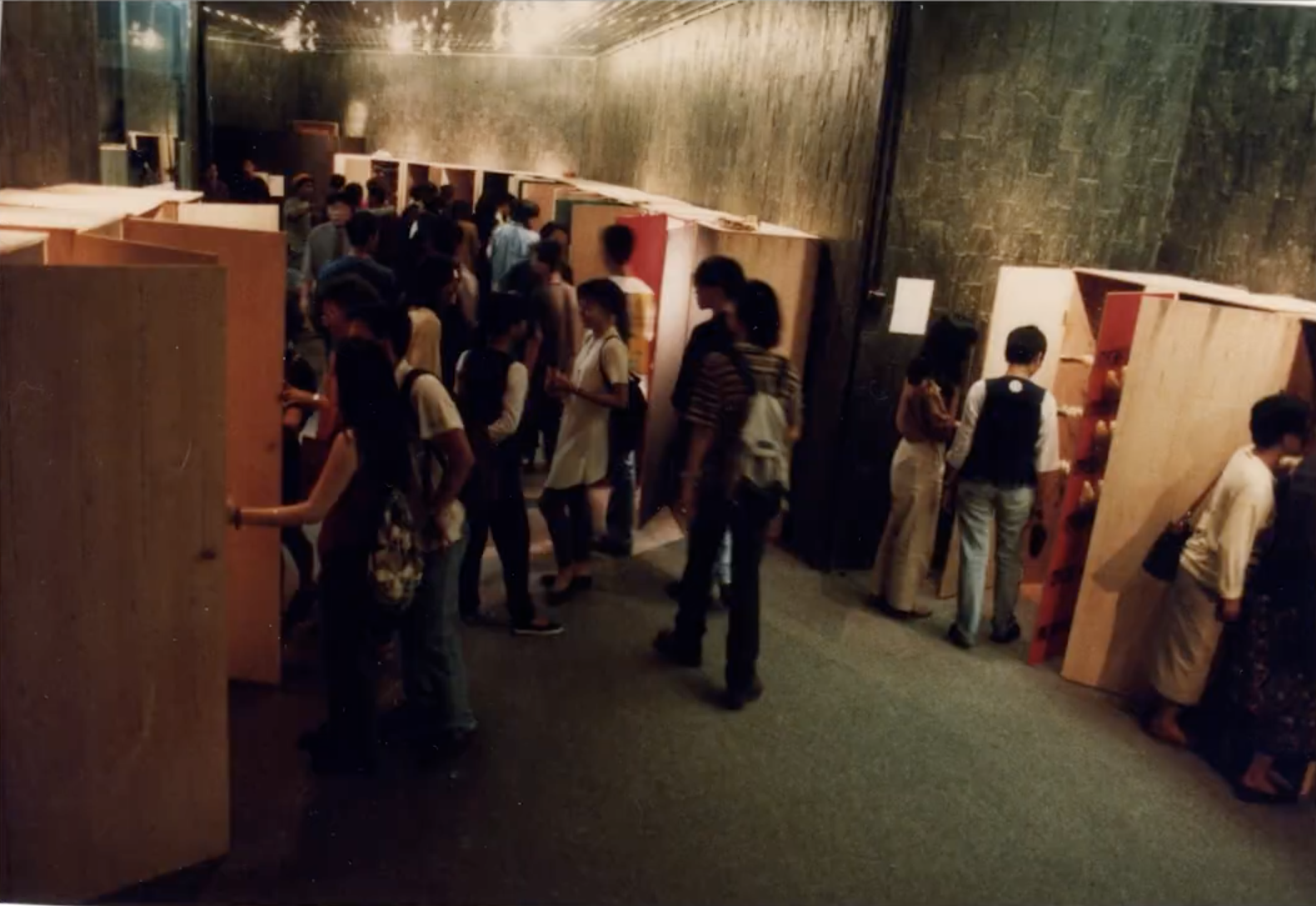

This art collective was brought to the public eye in 1991, where Victor’s efforts, along with fellow female artists Susie Lingham, Catherine Tan, and Han Ling, to ‘bringing art to the public’ finally manifested itself in the form of the 5th Passage, where they aspired to develop art in, with, and for society. Situated in the then-modern hub of social gathering: the urban shopping mall, specifically Parkway Parade, Victor foresaw the possibilities of a unique artist-led space that could nurture and develop alternative practices that prioritised experimentation and direct exposure and interaction with the masses, something that has become increasingly controlled by government bodies in Singapore’s contemporary landscape; as many art initiatives are increasingly mediated by institutional or government frameworks in Singapore’s contemporary landscape. The emphasis on bringing art to the public was an initiative that strived to break boundaries between the mundane and extraordinary. Such coexistence of art and life provided a space for the public to transform their perceptions and experiences toward their own lives.

Victor had a vision to transform the fifth-floor passageway of Parkway Parade’s Office Tower Block into that of a contemporary gallery and performance space. It represented a hope; a passage to a future of the arts, to de-mystify the arts to the masses. A vibrant platform for multidisciplinary artists to embrace their voice and courage in creativity in a living breathing space of newness is created. This allowed the public to thrive and immerse themselves with the notion of expression.

The art collective saw successes between the years 1991 and 1994, arranging multiple art projects that involved the participation of the public. By 1993, the 5th Passage had even found support in the form of government grants to realise larger scaled projects, a relatively new initiative by the then-newly established National Arts Council (NAC), founded in October 1991. The collective’s success as an independent and non-profit experimental collective attracted fellow artists and non-artists alike, who volunteered to support the collective. Names such as Noor Effendy, Daniel Wong, Henry Tang, Lee Wee Yan, and Iris Tan would be seen within the collective’s efforts, eventually inviting high-profile names from the NAC and National University of Singapore (NUS) to serve as founding advisors. Indeed, an impressive feat for such a young initiative at the time. As young artists, we ponder on the arts that we live with in Singapore today, and Fifth Passage is nothing quite alike as more contemporary art spaces continue to be sectioned away from public spaces as controlled by government bodies.

Such diversity and freedom in a Singapore that came before us despite a more conservative time seems so foreign and surreal in today’s landscape. Powerful voices from young contemporary artists that resonate with the audience, reflecting their response and navigation in a modernising society. Parkway Parade represented promise, a newness, a revolution.

Still Life, 1992

The 5th Passage would become known for their practices that challenge traditional hierarchy and patriarchy. Founded by a group of young female artists, Victor’s works and experimentations in the collective gave rise to forms and spaces that redefined such themes, along with blurring the lines and definitions of performance art in Singapore. Victor long saw the phallic nature of eggplants, redefining them into a symbol and metaphor for power and patriarchy. Inserting an ephemerality to the work, the installation is in a state of flux as the eggplants turn flaccid and droop upon each different viewing of the work. Through her re-contextualisation, she challenges viewers to rethink symbols of authority and question ingrained gender dynamics.

Chapter 3: The Abject

Suzann has placed much emphasis on the word “Abject” in descriptions of her artworks, themes, as well as her experience regarding the aftermath of the 5th Passage. The term ‘abject’ refers to rejection, expulsion, exile. This term was explored by theorist Julia Kristeva, it is associated with psychological disruption and societal unrest; evoking discomfort and even fear. Kristeva’s theory suggests that the abject exists at the border between the self and what is cast off—bodily fluids, death, taboo acts, things that threaten the coherence of identity and social order. What occurred on 1st January 1994 is often viewed as an unfortunate coincidence. For the media happened to capture the happenings of that day. What was meant to be a powerful performance by a now powerful international artist was twisted and turned into one that was labelled as offensive and controversial. The bustling life of the 5th Passage and public art projects and spaces that was gradually being built faced a sudden setback.

Therefore, an abjection, alienation even, occurred at that time as Victor and her fellow artists endured a deeply traumatic experience as the 5th Passage and her artists became the subject of mockery; exiles of Singaporean society. A group of young female artists at the time, shunned from society. Similarly, the abject affected the intangibility of the space.

As artists of the younger generation, the physical evidence we can derive of this abjection is through Parkway Parade today. Specifically the fifth level, has transformed into a transitional space, a void. The emptiness evokes a loneliness; upon entering the space, it feels as if the life, a history of the space, has vanished. Together with the 5th passage, Parkway Parade has also endured its exile. It served as a connecting vessel between life, art and people. This space felt eerily devoid of life, as if a memory were being preserved through absence. Potted plants are arranged evenly along the corners, a failed subtle attempt to revitalise the space. A stark contrast to Victor’s projects and career past the 5th Passage. This sense of suspended time, this holding of space in desolation, prompted a deeper consideration of how memory inhabits and shapes our environments. It was precisely within this context of absence, these lingering echoes of a former vitality are worth exploring

Suzann revisited the material of eggplants, along with its memory from the 5th Passage through the artwork Cast life, 2021. However, coating them in aluminium and clustering them in a suspension suggests an inevitability of power through the strong metallic appearance and their number. However, the performative element of eggplants is derived from their organic form. As the vegetable deteriorates and shrivels overtime, their phallic structure turns flaccid as they lose their ripeness and eventually decay. However, it is not observed through colour but through form. The collective crumpling and drooping of the coated structure in aluminium may suggest a memory being lost but trying to be preserved. The powers and structures that enabled 5th Passage to create space for alternative voices were also the ones that, under societal and institutional pressure, contributed to its silencing and eventual disappearance.

Suzann Victor, Cast life, 2021

Suzann Victor, Bloodline of Peace , 2015

Suzann Victor’s memory of the happenings of the 5th Passage have left her deeply impacted. We observe this by drawing connections between her current works and the now devoid space of Parkway Parade.

We take a look at Bloodline of Peace (2015), reflecting Singapore’s plight to independence, how, in order to achieve peace, it resulted in loss, violence, and pain through war and conflict. This need for peace to be exiled in order to achieve peace reflects a double standard in our society at the time that is being tackled through material in this artwork. 11,250 Fresnel lenses are assembled in a manner that looks fluid and flowing, embodying the essence of a cloth— soft and delicate. Each fresnel lens contains blood from donors in Singapore. 11,250 people, blood droplets, masked through the reflective, glasslike installation.

A familiarity can be drawn with the image of the ceiling in Parkway Parade. The structure of the glass ceiling, reflecting natural light through their angled geometric structure, corresponds to the arrangement of the fresnel lenses in Bloodline of Peace. The artwork installation is being swept up from the ground and hung like a tapestry on the ceiling, reflecting the similar transparency and reflective visual aesthetic of the glass ceiling architecture in Parkway Parade. Reflecting on peace and suffering in Singapore, we look into the courage, resilience, and challenges Suzann Victor has faced through her passion for reviving the arts in Singapore. The memory stays imprinted through her works as she continues to respond subconsciously and express her experiences, and continues to contribute to the evolving artistic landscape.

Conclusion

Such dynamism that emerged in early 1990s Singapore, marked by bold experimentation and grassroots-led art initiatives has long been forgotten or even frowned upon. Despite Suzann Victor’s well-meaning intentions and deep-rooted love for her community, the legacy of 5th Passage has been overshadowed by increasing restrictions on artistic expression following the 1994 performance art ban. One can’t help but wonder: if such radical creativity were to resurface today, would Victor and her peers be welcomed to express and cultivate a similarly vibrant art scene in this nation once more? Or must we continue reconciling with this history as an abject...something cast out, repressed, but never quite erased?

Ceiling Architecture of Parkway Parade, 2024